By: Dr. Claire Wells, DC

Chiropractor, Peak Health Elbow, Calgary, Alberta.

If you’ve ever had pain on the bottom of your heel, you’ve probably been told (or with the help of Dr. Google you’ve told yourself) that you have plantar fasciitis. And you could be right! In this post I’m going to break down the basics of this condition, and what we can do about it. Let’s dive in!

Anatomy Overview

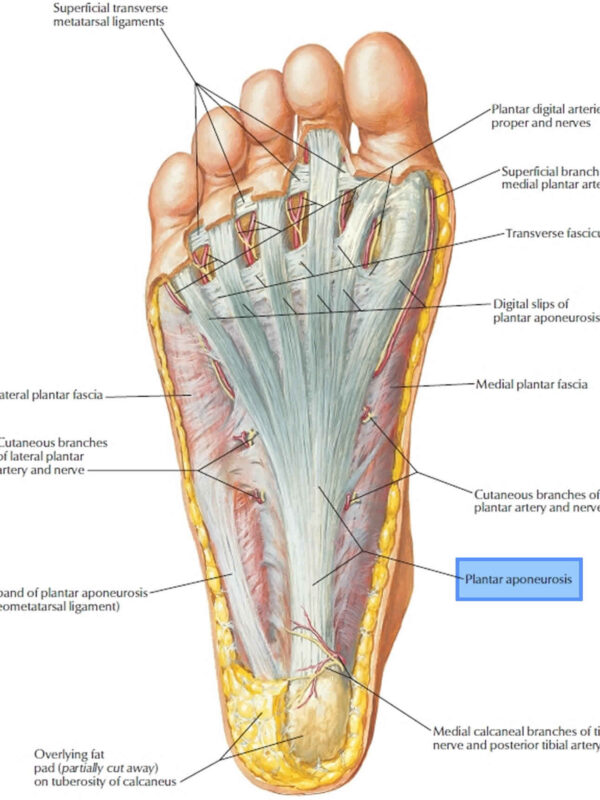

When there is pathology in the plantar fascia, we are specifically referring to a section called the “aponeurosis.” Almost always, there is degeneration of this tissue, as opposed to inflammation. This means the term “fasciitis” is not very accurate (“-itis” indicating inflammation), and “fasciopathy” is more appropriate (“-opathy” indicating an injury or problem with a tissue).

The plantar aponeurosis originates from the calcaneal tubercle (a bump on the bottom of the heel bone) and extends to the forefoot. In the forefoot, it divides into five separate bundles, which attach to the closest part of the toes. The plantar aponeurosis is not identical to a tendon or a ligament – it’s somewhere in-between, and is comprised largely of type 1 collagen. (1)

Fascial Function

The plantar aponeurosis supports the bottom of the foot, especially the medial arch. It plays an important role in turning the foot into a rigid lever during the push-off (“propulsion”) phase of walking and running.(2) But it doesn’t work alone! Other structures support the medial arch as well, including muscles. Strength of these muscles is critical for foot stability, and for preventing the aponeurosis from being over-stressed. Eccentric strength, which is when a muscle is lengthened under load, is especially important, since walking and running involve a lot of joint deceleration.

When walking or running, the aponeurosis and the associated muscles become tensioned when the big toe extends. This is called the ‘windlass mechanism’ and is critical for efficient movement.(2) Ensuring that we have good range of motion and strength of the big toe is important for healthy plantar fascia.

So what is plantar fasciopathy?

The problem is excessive biomechanical strain at the insertion of the aponeurosis on the heel bone. When the demands on the tissue exceeds the tissus ability to heal, we get tissue breakdown, or degeneration, and sometimes pain. Inflammation does not typically occur.

What are the risk factors for developing plantar fasciopathy?

The following factors can be associated with plantar fasciopathy(3, 4). The bold ones are factors that are modifiable (which is great news!). It’s important to realize that if any of these apply to you, it does not mean that you will get plantar fasciopathy, nor does it mean that you can’t do anything about it if you do get it.

- BMI >27

- Excessive running or a recent significant increase in weight-bearing activity

- Intrinsic foot muscle and calf muscle tightness

- Reduced ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, and/or excessive plantarflexion range of motion

- Weak calf muscles

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Metabolic conditions such as Type 2 Diabetes

- Acute increase in loading/exercise

- Leg length discrepancy

- Femoral or tibial torsion (This means an excessive structural twisting of the thigh or shin bone; this is something that we cannot change. But having this anatomical variation does not mean you are doomed!)

- Occupations that require prolonged periods of walking or standing

- High arches

- Low/flat arches

How Do I know if I might have plantar fasciopathy?

Classic signs of plantar fasciopathy include(3, 4):

- Pain located at the bottom of the heel, or where your heel and arch intersect

- Usually affects only one foot

- Worse first thing in the morning, or with the first steps after being prolonged rest (especially if your ankle has been in plantar flexion, aka pointed downwards). It may also be worse in the evening.

- Pain is sharp or stabbing, and does not radiate

- No tingling or pins and needles

Do I need to get diagnostic imaging?

X-rays can’t help us, because this is not a bone problem. Ultrasound and MRI can show the density and thickness of the fascia, but we don’t need that information to diagnose the condition or predict prognosis. So, diagnostic imaging is not necessary unless other injuries like a fascial rupture or a calcaneal stress fracture are suspected.(4)

X-rays can’t help us, because this is not a bone problem. Ultrasound and MRI can show the density and thickness of the fascia, but we don’t need that information to diagnose the condition or predict prognosis. So, diagnostic imaging is not necessary unless other injuries like a fascial rupture or a calcaneal stress fracture are suspected.(4)

Differential Diagnoses: What else could my plantar heel pain be?

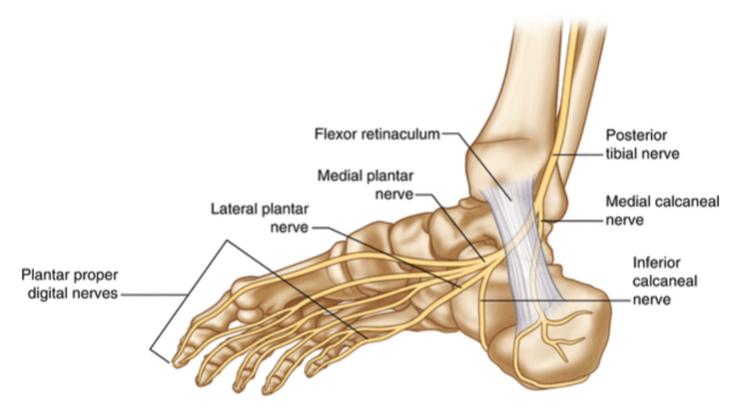

“Plantar” refers to the bottom surface of the foot. Not all pain on the bottom of the heel is plantar fasciopathy! Other causes of pain in this region can be misdiagnosed as plantar fasciopathy, and thus may end up being treated ineffectively. Peripheral nerve entrapment is a big one. This is when one of the nerves that supplies the bottom of the foot is compressed, or otherwise biomechanically irritated. If this is the cause, you might only get pain, but you might also get numbness, pins and needles, tingling, or burning or electric-like pain. You may also feel worse during or after stretching, or rolling out the bottom of the foot. Nerve pain could also be originating from the low back, so it’s important to rule out the spine as the culprit. Sometimes you can get plantar heel pain from muscle tightness or trigger points. Other less common conditions that can cause pain in this area include tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction, calcaneal stress fracture, insertional achilles tendinopathy, Sever’s apophysitis, calcaneal fat pad atrophy, and inflammatory arthropathy.

Sometimes you can get plantar heel pain from muscle tightness or trigger points. Other less common conditions that can cause pain in this area include tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction, calcaneal stress fracture, insertional achilles tendinopathy, Sever’s apophysitis, calcaneal fat pad atrophy, and inflammatory arthropathy.

If I have plantar fasciopathy, what can I do about it?

Ensuring that you see a practitioner who can assess your specific case and prescribe an individualized exercise program for your mobility and stability needs is an important step in tackling your pain.

You may need initial activity modification to reduce pain, but gradual overload of the tissue is required to promote healing and build up capacity for loading. Being out of pain does not equal being ready to immediately dive right back into high activity levels.

Addressing factors that may have contributed to this in the first place is important. Do you have good foot stability and control? If not, you might rely too much on passive structures like the plantar aponeurosis. Do we have good trunk and lower limb stability and control? If not, the whole posterior chain may over-work and tense up, which may cause nerve or muscle tension as far down as the calf and foot.

Treatment Options for Plantar Fasciopathy

Usually for long-term success, we need to work on intrinsic foot muscle strength, and big toe mobility and strength. But when it comes to treatment that targets the plantar fascia itself, we have research-based exercise protocols that improve function and reduce pain. Keep in mind that because this is a degenerative condition of connective tissue (which takes longer to heal), you will have to be patient with the recovery process. It’s not going to go away within a few days!

When it comes to pain and function, we have a hierarchy of interventions.

- Strengthening the plantar fascia is superior to…

- Stretching the plantar fascia, which is in turn superior to…

- Stretching the Achilles tendon/calf muscles

Good strengthening requires that we get tension in both the Achilles and the plantar aponeurosis, by activating the windlass mechanism. You’ll recall that the windlass mechanism is when big toe extension tensions the aponeurosis and muscles of the medial arch. We invite the Achilles tendon to the party to further increase fascial tension – this works because these two connective tissue structures are, well, connected! (1)

Where to Start:

Single leg calf raises, with the toes supported in maximal extension is a great place to start.(6) There is a specific loading protocol that research has shown to be effective, but it’s best to see your chiropractor or physiotherapist for an exercise program that is tailored to your specific needs. The studies on this used a 12-week program, which is important to keep in mind. It takes time for the tissue to adapt, even if you start to see improvement in pain before 12 weeks.

Shockwave therapy, laser therapy, orthotics, dry-needling, taping, and other techniques provided by chiropractors and physiotherapists can be helpful for improving pain and function, as adjuncts to exercise.

What about injections?

A systematic review and meta-analysis found no high-quality evidence to show that corticosteroid injections are better than other forms of treatment for improving pain and function in the short, medium, or long-term.(9) They have similar outcomes to placebo injections (which means that a real corticosteroid injection was not better than a fake one). They also result in total rupture of the fascia in 2-10% of cases.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) vs. corticosteroid injections found that PRP is better at reducing pain, however, the quality of the studies was generally low and the injection protocols were highly variable, so these results must be viewed with caution.(10)

Overall, I recommend trying conservative treatment first, such as chiropractic or physiotherapy. PRP may be something to consider for severe and/or chronic, unremitting pain.

Take-home points:

-

Plantar heel pain is not always plantar fasciopathy. Get assessed to make sure

-

The plantar aponeurosis needs help from the muscles of the foot, and good mobility of the big toe, in order to function well

-

Treatment may need to address more than just the foot itself

-

Strengthening is the best treatment! This tissue requires intentional loading to recover properly

References:

- Stecco C, Corradin M, Macchi V, et al. Plantar fascia anatomy and its relationship with Achilles tendon and paratenon. J Anat. 2013;223(6):665-676. doi:10.1111/joa.12111

- Wearing SC, Smeathers JE, Urry SR, Hennig EM, Hills AP. The pathomechanics of plantar fasciitis. Sports Med. 2006;36(7):585-611. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636070-00004.

- Trojian T, Tucker AK. Plantar Fasciitis. Am Fam Physician. 2019 Jun 15;99(12):744-750. PMID: 31194492.

- Monteagudo M, de Albornoz PM, Gutierrez B, Tabuenca J, Álvarez I. Plantar fasciopathy: A current concepts review. EFORT Open Rev. 2018 Aug 29;3(8):485-493. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170080.

- Menz HB, Thomas MJ, Marshall M, Rathod-Mistry T, Hall A, Chesterton LS, Peat GM, Roddy E. Coexistence of plantar calcaneal spurs and plantar fascial thickening in individuals with plantar heel pain. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019 Feb 1;58(2):237-245. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key266. PMID: 30204912; PMCID: PMC6519610.

- Rathleff, M. et al. “High‐load strength training improves outcome in patients with plantar fasciitis: A randomized controlled trial with 12‐month follow‐up.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 25 (2015)

- Riel H, Jensen MB, Olesen JL, Vicenzino B, Rathleff MS. Self-dosed and pre-determined progressive heavy-slow resistance training have similar effects in people with plantar fasciopathy: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2019 Jul;65(3):144-151. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2019.05.011. Epub 2019 Jun 13.

- Salvioli S, Guidi M, Marcotulli G. The effectiveness of conservative, non-pharmacological treatment, of plantar heel pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Foot (Edinb). 2017 Dec;33:57-67. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2017.05.004. Epub 2017 Jun 15. PMID: 29126045.

- Whittaker GA, Munteanu SE, Menz HB, Bonanno DR, Gerrard JM, Landorf KB. Corticosteroid injection for plantar heel pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019 Aug 17;20(1):378. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2749-z. PMID: 31421688; PMCID: PMC6698340.

- Hohmann E, Tetsworth K, Glatt V. Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Corticosteroids for the Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2021 Apr;49(5):1381-1393. doi: 10.1177/0363546520937293. Epub 2020 Aug 21.