By: Dr. Claire Wells, Chiropractor

Running is one of the most accessible forms of exercise, and a great way to enjoy being outside during these remaining weeks of good weather in Calgary. Because so many people run, there is a lot of information that circulates on social media, in marketing campaigns, and even by word of mouth, about what we “should” do when it comes to running. But not all information is good information, so below I bust four common running myths to help you get the most out of the season!

MYTH 1: “You should minimize rotation of the trunk and arms.”

When I started running, I was certain that rotating my body was bad. I was told it was a waste of energy; that my arms should never stray from straight, and my hips should always face perfectly straight forward. I was so proud when I would go for a run and keep my trunk super rigid and stiff.

But wow, was I wrong! As it turns out, running is a rotational sport. Controlled rotation throughout the body is how we propel ourselves forward. Let me explain…

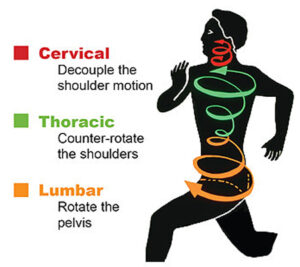

It would be easy to think of the legs as being our primary drivers for moving our body forwards when we run (after all, that’s what it looks like!). But even if you had no legs, you would be able to “walk” by reciprocal rotation of the pelvis (driven by the lumbar spine, AKA the low back) and the shoulders (driven by the thoracic spine AKA the mid and upper back).

[Image1]

“It’s important to realize that trunk, hip, knee, ankle, and foot rotation is normal and necessary to run efficiently. And efficiency means reduced injury risk.”

This is not to say that the legs don’t matter! Even though the trunk is our driving force, the legs play a huge role in running, and they also must rotate. It’s important to realize that trunk, hip, knee, ankle, and foot rotation is normal and necessary to run efficiently, which means reduced injury risk.

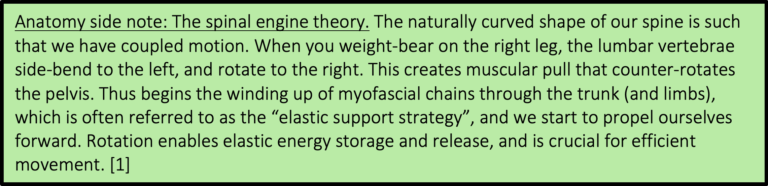

Now, this doesn’t mean we should go out and run like a wacky inflatable tube man, flailing our body parts into twisting motions. There is such a thing as unhelpful rotation (if it’s not producing momentum to propel us forward, it’s not helpful), so there is a sweet spot when it comes to how much rotation we produce at each level of the body. And most importantly, if we do not have control of the ranges we use when running, we are setting ourselves up for some problems.

[Image2]

My Advice:

Be able to resist rotation before you can expect to create it efficiently and be able to control the range of motion available to you. This means doing specific exercises to build up your capacity (and yes, you need to strength train if you are a runner!). It’s best to see a chiropractor or physiotherapist in Calgary who can identify deficiencies specific to you, and prescribe exercises accordingly but here are a few examples:

• Core/trunk: Paloff press, bear plank or high plank shoulder taps, cable chops and lifts

• Hip: single leg Romanian deadlifts, hip airplanes, 90-90 get-downs, rotational cable squats

• Ankle and foot: banded supinations, ankle rocker board, active inversion-eversion

Unlike me when I started running, don’t think you need to keep your shoulders and hips rigidly facing forward when you run. Let your “spinal engine” do its thing!

MYTH 2: “You should forefoot strike to reduce impact on your joints”

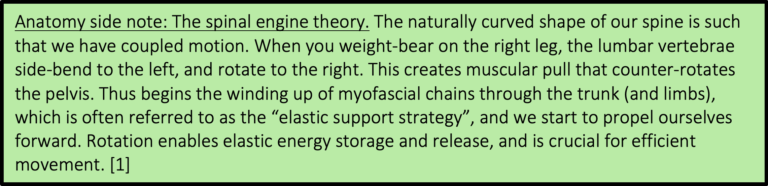

You may have heard that landing on your heel is “bad for your joints,” or even just that it’s inefficient. Don’t believe the lies, friends! There is no inherently superior strike pattern during running.

Our bodies are smart, not to mention highly variable in individual anatomy, and your body will self-select the strike pattern that is mechanically efficient for you. Speed of running will also change this. Until you reach a 6:00-6:30 minute-mile pace, heel striking is more efficient for most people. At that pace, heel and midfoot striking are about equally efficient. Most elite marathoners midfoot strike because they are running so fast. Similarly, you’ll notice that sprinters are always landing on the forefoot, out of necessity, because of their speed.

Slow running is more efficient with heel striking. This means runners who naturally heel strike should not try to intentionally forefoot strike. Doing so may overload the gastrocnemius (not as well designed to absorb force) and can lead to posterior calf (and Achilles tendon) injury.

[Image3]

When we change our strike pattern, we change what structures are predominantly absorbing the force, but we do not change how much force the body needs to absorb. [4]

• Forefoot strike: ankles and calves

• Midfoot strike: foot arches and tibialis posterior

• Heel strike: knees and tibialis anterior

So, good news: There is no difference in injury rate between forefoot and rearfoot striking, and there is no association between foot strike pattern and performance. [2, 3, 7] Thus, no need to force yourself to change what you do.

Note: I am not advocating that everyone heel strike, just recommending that you don’t try to intentionally change your heel strike pattern, unless you have significant knee pain, for example. But if that’s the case, see a chiropractor or physiotherapist!

My Advice:

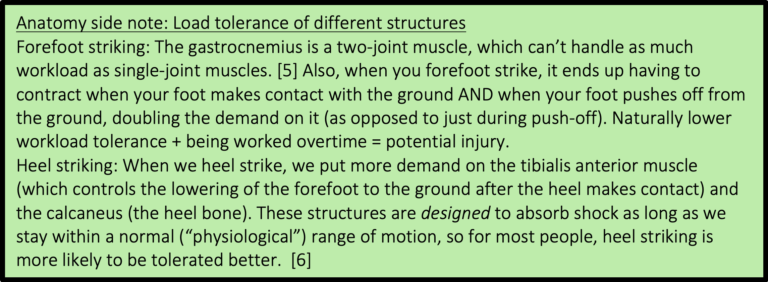

What most research seems to support is that what we should care about, more than foot strike, is the angle of the tibia (the shin bone) when we make contact with the ground. We want to see at most a 7-degree angle in front of vertical. Vertical, as in the shin being perpendicular to the ground (or straight up from the foot to the knee), is ideal. Not sure if you do this? Try having someone film you running, take some screenshots, and then use a free app like Technique or Hudl to draw angles on the photo.

[Image4]

MYTH 3: “You should wear a supportive shoe to minimize risk of injury”

Ultra-cushioned and motion-control shoes are becoming more popular because marketing campaigns have us believing that they can better attenuate shock, and thus reduce injuries. But…do they? Let’s take a look at some research…

[Image5]

“Extra cushioning interferes with proprioception, and therefore slows reaction time. This means our ability to stabilize and control our lower extremity is compromised, and you may get injuries higher up the chain.”

One study found that in the ultra-cushioned shoes, the timing was off for normal joint motion between the calcaneus (heel bone) and tibia (shin bone). This resulted in increased rotational stress on the knee, which may contribute to knee injury.

→ Super-cushioned shoes are unlikely to benefit your mechanics in a way that is protective or advantageous. [8]

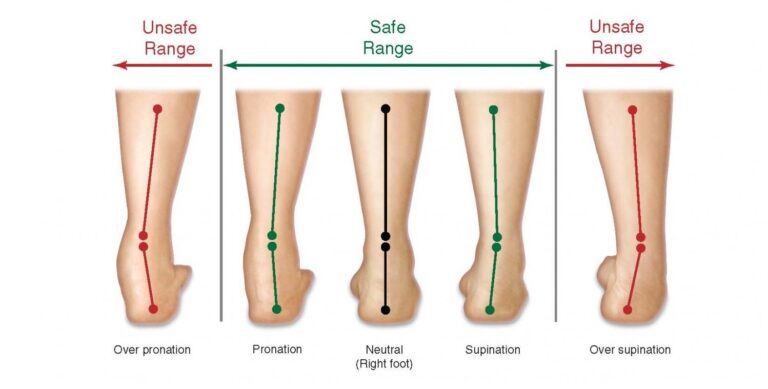

One study followed 952 runners for a year. They all ran in a neutral running shoe, regardless of their foot type, and there was no significant difference in the risk of sustaining an injury for any foot type. This makes sense because foot type is NOT consistently associated with injury rates in research. [9]

In a study that followed runners training for a half-marathon, they found that those wearing the motion control shoes had significantly greater pain, regardless of foot type.

→ They concluded that picking shoes based on stability categories does not reduce the risk of running pain. [11]

This might go against what seems intuitive, which is that sloppy feet need to be controlled. But, excessive cushioning decreases the foot’s ability to get sensory information and send it to the brain. Reduced sensory input to the brain equals reduced quality of motor output (we can’t react to what we don’t know). We need constant feedback of impact forces and foot position to control ourselves. [10]

For this reason, it makes sense that wearing a highly motion-controlled or cushioned shoe could actually be WORSE for someone with feet that pronate too early or for too long. Extra cushioning interferes with proprioception, and therefore slows reaction time. This means our ability to stabilize and control our lower extremity is compromised, and you may get injuries higher up the chain.

My Advice:

The take home here is that you don’t need a specific type of shoe for a specific type of foot. Just buy shoes that feel COMFORTABLE. Your toes should be able to splay within the shoe, so if you can get a wide toe box on your shoes, even better.

MYTH 4: “You should stretch to prevent injuries”

NO studies have shown that “acute stretching,” aka stretching right before a run, improves running performance. It might actually decrease it! And long-term stretching doesn’t seem to make for better running, either.

Here are some brief examples based on research: [12]

• Stiffer thigh and calf muscles equals better force transfer between the deceleration and push-off phases.

• Less flexible hip and calf means less muscular effort needed to stabilize during foot strike

• 10 weeks of stretching resulted in no improvement in running efficiency, and no reduction in injury incidence. In this case, the stretching was even done separately from running.

• Gene COL5A1 is associated with inflexibility, and is found in elite endurance (runners with this gene had significantly higher running efficiency than others in one study)

• Stretching has no effect on chronic injury prevalence in runners

[Image6]

Elastic energy is what makes running efficient. The changes that occur from stretching reduce our ability to store and release elastic energy. So, we need more muscular effort to stabilize our joints.

High muscular effort = more oxygen needed = it takes more work to run!

This applies to stretching right before a run, and also long-term. Now, this doesn’t mean nobody should stretch. It really depends on how much range of motion you already have (and control of that motion, like I mentioned in Myth 1). There is a sweet spot, where you have enough range of motion to allow for the required movement, but not so much that we sacrifice elastic energy.

Another interesting thing to note is that there is also no evidence that stretching has the ability to reduce the severity or duration of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). So, for most of us, stretching is not going to prevent injuries, increase performance, or reduce soreness. But sometimes it feels good to do!

My Advice:

Go ahead and stretch if it feels good for you, but I’d recommend against doing a ton of it, and definitely not before a run, in the name of mechanical efficiency. Your time could be better spent on other activities to support your running goals.

Take-home points:

1. Let your body rotate while running

2. Don’t force a specific foot strike

3. When choosing shoes, just go with what feels comfortable

4. Stretching does not make you faster or less likely to be injured

These are general principles that will apply to most people, but if you are a runner and you’re experiencing pain or have questions about what running factors are specific to you, it’s best to get assessed by a chiropractor or physiotherapist. Our teams at Peak Health Elbow and Peak Health Marda will get you back to that runner’s high and you can book online here.

References:

1. Gracovetsky, Serge. (1997). Linking the spinal engine with the legs: a theory of human gait. Movement, Stability and Low Back Pain – The Essential Role of the Pelvis.

https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/52884/file-5411457.pdf/2012%20NCAA%20Indoor%20Track%20Championships

2. Kasmer ME, Liu XC, Roberts KG, Valadao JM. The Relationship of Foot Strike Pattern, Shoe Type, and Performance in a 50-km Trail Race. J Strength Cond Res. 2016 Jun;30(6):1633-7. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a20ed4. PMID: 23860289.

3. Kasmer ME, Liu XC, Roberts KG, Valadao JM. Foot-strike pattern and performance in a marathon. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2013 May;8(3):286-92. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.8.3.286. Epub 2012 Sep 19. PMID: 23006790; PMCID: PMC4801105.

4. Kleindienst F, Campe S, Graf E, et al. Differences between fore- and rearfoot strike running patterns based on kinetics and kinematics. XXV ISBS Symposium 2007, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

5. Hasselman C, Best T, Seaber A, et al. A threshold and continuum of injury during active stretch of rabbit skeletal muscle. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:65-70

6. Cunningham C, Shilling N, Anders C, et al. The influence of foot posture on the cost of transport in humans. J Experimental Biol. 2010;213:790-797.

7. Miller R, Russell E, Gruber A, et al. Foot-strike pattern selection to minimize muscle energy expenditure during running: a computer simulation study. Annual meeting of American Society of Biomechanics in State College. PA 2009.

8. Brianne Borgia, Julia Freedman Silvernail & James Becker (2020): Joint coordination when running in minimalist, neutral, and ultra-cushioning shoes, Journal of Sports Sciences, DOI: 10.1080/02640414.2020.1736245.

9. Nielsen RO, Buist I, Parner ET, Nohr EA, Sørensen H, Lind M, Rasmussen S. Foot pronation is not associated with increased injury risk in novice runners wearing a neutral shoe: a 1-year prospective cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Mar;48(6):440-7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092202. Epub 2013 Jun 13. PMID: 23766439.

10. Richards, C E; Magin, P J; Callister, R (2009). Is your prescription of distance running shoes evidence-based?. , 43(3), 159–162. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.046680.

11. Ryan MB, Valiant GA, McDonald K, et alThe effect of three different levels of footwear stability on pain outcomes in women runners: a randomised control trialBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2011;45:715-721.

12. Claire Baxter, Lars R. Mc Naughton, Andy Sparks, Lynda Norton & David

Bentley (2016): Impact of stretching on the performance and injury risk of long-distance

runners, Research in Sports Medicine, DOI: 10.1080/15438627.2016.1258640

Media References:

• [Image1] https://erikdalton.com/blog/legs-really-necessary/

• [Image2] https://www.tunnelmarathon.com/blogs/news/counter-rotation-exercises-for-runners

• [Image3] https://www.roadrunnersports.com/blog/running-foot-strike/

• [Image4] https://www.nurvv.com/en-us/support/footstrike/

• [Image5] https://supinate.wordpress.com/tag/supination/

• [Image6] https://www.womenshealthmag.com/uk/fitness/running/a706581/best-calf-stretches-for-runners/